Entrepreneurs

If in doubt, innovate

The Nordic region is becoming a hothouse of entrepreneurship

IN 2010 A GROUP of students at Aalto University, just outside Helsinki, embarked on the most constructive piece of student activism in the history of the genre. They had been converted to the power of entrepreneurialism during a visit to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. When they got home they organised a “summer of start-ups” to spread the word that Finland’s future lay with new companies, not old giants. The summer of start-ups turned into a season of innovation.

The Start-Up Sauna—a business accelerator that is still run by young enthusiasts but now funded by government, business and academia—occupies a dilapidated warehouse next to the university. It offers a wide range of services: working space, coaching for budding entrepreneurs, study trips to Silicon Valley and plenty of networking opportunities (including in the Sauna’s many saunas).

The Sauna-masters have an understanding of entrepreneurship in advance of their years. They recognise that there is more to innovation than high tech: the Sauna also has design and knitting factories. They understand the importance of bridging the gap between engineering and design. They realise that promoting entrepreneurship is a matter of changing culture as much as providing money. They look to Russia and the Baltic states as well as to Boston and San Francisco.

No more Nokias

The student revolution was part of a wider reconsideration of the proper relationship between government and business. This had started in 2008, when the Finnish government shook up the universities (and created Aalto) in an attempt to spur innovation. But it was speeded up by Nokia’s problems. Finland had become dangerously dependent on this one company: in 2000 Nokia accounted for 4% of the country’s GDP. The government wanted to make the mobile-phone giant’s decline as painless as possible and ensure that Finland would never again become so dependent on a single company.

The Finns created an innovation and technology agency, Tekes, with an annual budget of €600m and a staff of 360. They also established a venture-capital fund, Finnvera, to find early-stage companies and help them get established. The centrepiece of their innovation system is a collection of business accelerators, partly funded by the government and partly by private enterprise, that operate in every significant area of business and provide potential high-growth companies with advice and support from experienced businesspeople and angel investors.

As a result, Finland has become much more market- and entrepreneur-friendly. It has produced an impressive number of start-ups, including 300 founded by former Nokia employees. Microtask outsources office work. Zen Robotics specialises in automating recycling. Valkee makes a device that lifts wintry dark moods by shooting bright light into the ear canal. The country has also acquired the paraphernalia of a tech cluster, such as a celebratory blog (Arctic Startup) and a valley-related name (Arctic Valley). The fashionable argument now is that Nokia’s decline is “the best thing that ever happened to this country”.

The new Finland is particularly proud of its booming video-games industry, including successful companies such as Rovio Entertainment, the maker of Angry Birds and a leading supporter of the Start-Up Sauna, and Supercell, the maker of Clash of Clans. Supercell’s employees are what you would expect: men with beards and ponytails who take time out from their computer screens to show off their collections of action figures.

Ilkaa Paananen, Supercell’s CEO, points out that Finland has spent years preparing for its current success. Helsinki started to host a festival for gamers in the early 1990s. Today the festival is so popular that the organisers have to rent the city’s biggest ice-hockey stadium, with room for 13,000, and still turn people away. Kajak University offers courses in video games. Finns have a comparative advantage in the four things that make for great games—blood-soaked storylines (all those sagas), bold design, ace computer programming and what might be politely called “autistic creativity”.

The arrival of the iPad and its apps allowed the Finnish industry to break out of its frozen ghetto. Mr Paananen says he now has the wherewithal to build the “company of my dreams”. Screens on the wall display how Supercell is doing against its rivals in real time. The games-masters talk about IPOs and “massive growth curves”. The company recently moved into new headquarters which, poignantly, used to be Nokia’s R&D centre.

The mood reflected in the summer of start-ups can be found across the region: investors everywhere are looking for new opportunities and bright young things are running companies in converted warehouses. Hjalmar Winbladh, one of Sweden’s leading entrepreneurs, says that the atmosphere has changed completely since he started out in business in the early 1990s. Back then people like him were oddities. Today fashionable young people worship successful tech entrepreneurs such as Niklas Zennström, the co-founder of Skype, and Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, the co-founders of Spotify. Mr Winbladh says that his biggest problem is to attract young talent from other start-ups. They all shudder at the thought of spending their lives in big organisations.

Nordic governments recognise that they need to encourage more entrepreneurs if they are to provide their people with high-quality jobs, and that they can no longer rely on large companies to generate business ecosystems on their own. They are creating government agencies to promote start-ups. They are encouraging universities to commercialise their ideas and generate start-ups. They are telling their schools to sing the praises of entrepreneurship.

Many of the region’s most interesting entrepreneurs operate at the low end of the tech spectrum, often to help parents deal with the practical problems of combining full-time work and family. Niklas Aronsson, co-founder of a company called Linas Matkasse, has applied IKEA’s do-it-yourself model to family dinners. He delivers bags containing all the ingredients needed for a meal, chopped up and ready to cook—a perfect solution for people who are short of time but prefer not to bring up their children on takeaway pizza.

Monica Lindstedt, founder of Hemfrid, is also in the business of selling time. She has turned her company into a house-cleaning giant, applying professional management to domestic cleaning and turning it into an employment perk. Hemfrid has persuaded the government to treat house-cleaning as a tax-deductible benefit, like a company car. It has also convinced companies that this is a great way to reward their employees and free them from domestic distraction. Hemfrid now has 10,000 regular customers and 1,326 employees, 70% of them born abroad.

Nordic entrepreneurs are also reinventing retirement homes for baby-boomers. A Finnish private housing association, Asunto Oy Helsingin Loppukiri, has built a housing community in the suburbs of Helsinki that is dedicated to the idea of helping people help themselves. The residents took an active part in designing both the buildings’ common areas (which include saunas and exercise rooms) and their individual flats. Most of them own shares in the company. It tries to offer a balance between independent living and community involvement. The members eat together once a week and tend a communal allotment whenever they feel like it.

Don’t go

Despite all this entrepreneurial energy, the Nordic region still finds it hard to turn start-ups into enduring companies. There are too many examples of successful entrepreneurs who have upped sticks and gone elsewhere. These include not just members of the post-war generation such as Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of giant IKEA (who lives in Switzerland), and Hans Rausing, the founder of Tetra Pak, a huge packaging company (who went to live in England), but also members of the up-and-coming generation. Mr Zennström, along with many of the brightest Swedish investors and entrepreneurs in his age group, lives in London. Too many successful start-ups still choose to sell themselves to foreign (mainly American) multinationals rather than becoming local champions.

Despite all its entrepreneurial energy, the Nordic region still finds it hard to turn start-ups into enduring companies

Still, there is reason to hope that the entrepreneurial boom will also produce a new generation of global champions. The region’s lifestyle entrepreneurs have a chance of becoming global moguls for the same reason that Mr Kamprad did: because they are riding the wave of demographic change. And the region’s high-tech entrepreneurs have a chance of founding enduring companies because they are building up businesses as well as mastering technology.

One example is Rovio Entertainment, which struck gold with Angry Birds, a game that involves catapulting irascible avians at elaborate fortresses constructed by evil pigs. It was downloaded more than 600m times in 2011. Having produced one big hit, most games companies would have started looking for the next one, but instead Rovio set about turning Angry Birds into a brand and extending its reach. It struck licensing agreements with a range of companies to make Angry Birds-branded products, from toys to chocolate to theme parks. It raised capital from outside investors such as Microsoft, which chipped in $42m. Rovio now has 500 employees in Finland and had a turnover of $100m in 2011. Michael Hed, the company’s CEO, has a traditional corner office, but it is full of stuffed birds and pigs.

The Economist

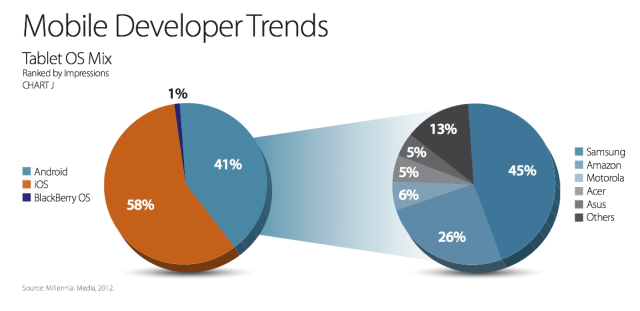

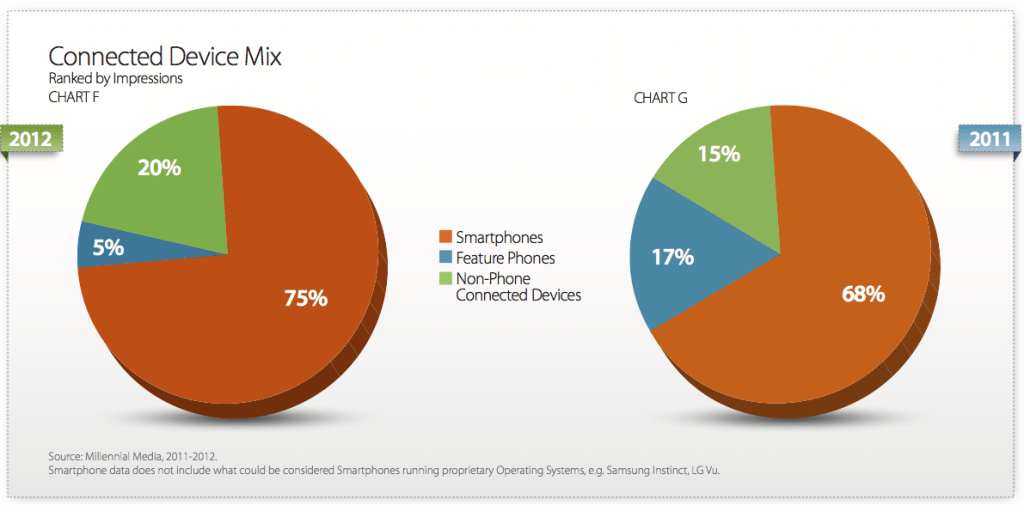

Millennial notes that Android continues to take up more places in the top 20 mobile phones list on its platform, while Apple continues to be the market leader with its devices in each respective category, generating an outsized helping of traffic share from just a few core devices. The iPhone ranks number one among mobile phones, growing its share from 14.67 percent in 2011 to 15.59 percent in 2012. Samsung took over the number two spot from BlackBerry with its Galaxy S line, with 4.24 percent of impressions for 2012, growing 182 percent year-over-year.

Millennial notes that Android continues to take up more places in the top 20 mobile phones list on its platform, while Apple continues to be the market leader with its devices in each respective category, generating an outsized helping of traffic share from just a few core devices. The iPhone ranks number one among mobile phones, growing its share from 14.67 percent in 2011 to 15.59 percent in 2012. Samsung took over the number two spot from BlackBerry with its Galaxy S line, with 4.24 percent of impressions for 2012, growing 182 percent year-over-year.

11:56

11:56

Juan MC Larrosa

Juan MC Larrosa

.png)